Brazil Twitter Files - Part 1

by Michael Shellenberger, X (@shellenberger), April 03, 2024

Brazil is engaged in a sweeping crackdown on free speech led by a Supreme Court justice named Alexandre de Moraes.

De Moraes has thrown people in jail without trial for things they posted on social media. He has demanded the removal of users from social media platforms. And he has required the censorship of specific posts, without giving users any right of appeal or even the right to see the evidence presented against them.

Now, Twitter Files, released here for the first time, reveal that de Moraes and the Superior Electoral Court he controls engaged in a clear attempt to undermine democracy in Brazil. They:

— illegally demanded that Twitter reveal personal details about Twitter users who used hashtags he did not like;

— demanded access to Twitter’s internal data, in violation of Twitter policy;

— sought to censor, unilaterally, Twitter posts by sitting members of Brazil’s Congress;

— sought to weaponize Twitter’s content moderation policies against supporters of then-president @jairbolsonaro

The Files show: the origins of the Brazilian judiciary’s demand for sweeping censorship powers; the court’s use of censorship for anti-democratic election interference; and the birth of the Censorship Industrial Complex in Brazil.

gMail users - Google has truncated this Newsletter,

please click the headline to view this newsletter in full online

TWITTER FILES - BRAZIL was written by @david_agape_ @EliVieiraJr & @shellenberger

We presented these findings to de Moraes, to the Supreme Court (STF), and to the High Electoral Court (TSE). None responded.

Let’s get into it...

“We are… pushing back against the requests...”

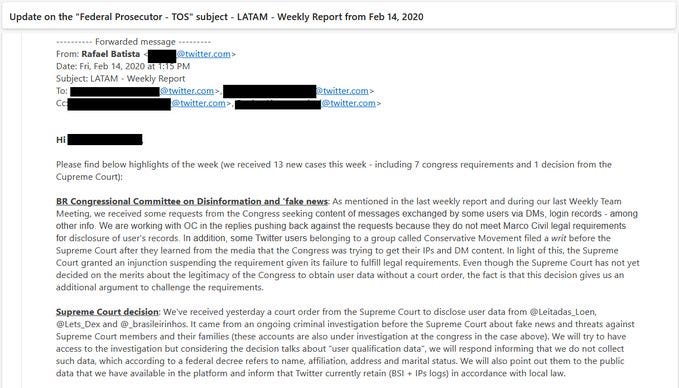

On February 14, 2020, Twitter’s legal counsel in Brazil, Rafael Batista, emailed his colleagues to describe a hearing in Congress on “Disinformation and 'fake news’”

Batista revealed that members of Brazil’s Congress had asked Twitter for the “content of messages exchanged by some users via DMs” as well as “login records - among other info.”

Batista said, “We are… pushing back against the requests,” which were illegal, “because they do not meet [Brazilian Internet law] Marco Civil legal requirements for disclosure of user's records.”

Batista noted that some conservative Twitter users had gone to the Supreme Court “after they learned from the media that the Congress was trying to get their IPs and DM content. In light of this, the Supreme Court granted an injunction suspending the requirement given its failure to fulfill legal requirements.”

CONTEXT: Brazil’s Supreme Court and Superior Electoral Court

Seven justices comprise Brazil’s Superior Electoral Court (TSE).

Three of those justices are also members of the Supreme Court (STF).

One of them, Alexandre de Moraes, presides over the TSE.

Here's background on the rise of Brazil's Censorship Industrial Complex by @david_agape_

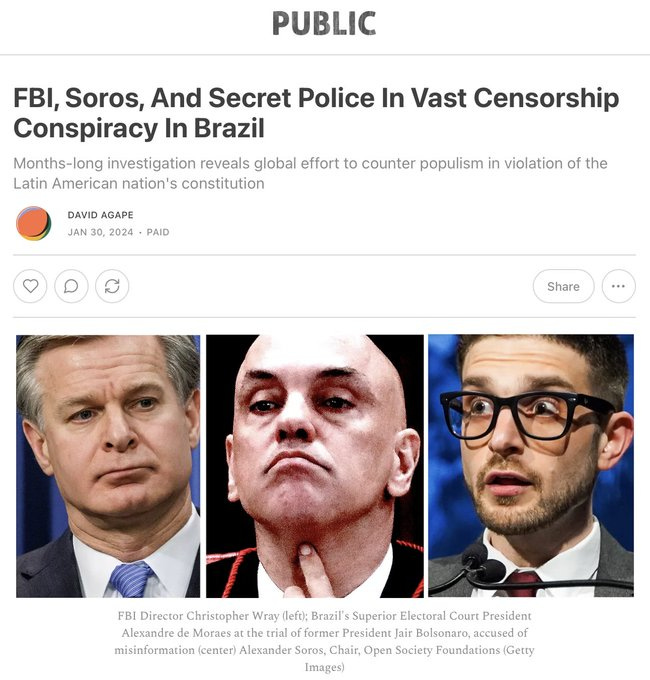

The FBI, George Soros, and Brazil's government say they defend free speech and democracy. But a new, months-long investigation finds that they have been secretly working together to oversee a mass censorship effort that is in direct violation of the US & Brazilian Constitutions.

The U.S. government’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), George Soros, and the Supreme Court of Brazil claim to be defenders of free speech and democracy. The mission of the FBI is to uphold the U.S. Constitution, whose First Amendment prohibits government limits on freedom of speech. Soros, and his son Alex, who runs his philanthropic foundation, claim to want to “open societies,” where people are free to express their views freely. And the Supreme Court of Brazil claims to uphold the Brazilian Constitution’s commitment to freedom of expression.

But now, a months-long investigation reveals that: the FBI has helped Brazil censor its citizens; the Soroses’ “Open Society Foundation” is spending heavily to promote censorship in Brazil; and Brazil has a secret judicial police force that exists specifically to spy upon and censor people deemed to be spreading false information. Together, the FBI, the Soroses, and the Supreme Court of Brazil are engaged in a direct assault on the free speech protections of both the Brazilian and U.S. Constitutions.

The FBI, Soros Foundations, and the Brazilian government all declined to be interviewed for this piece. And there are key elements of the Brazilian government’s censorship efforts that we do not understand.

But nobody doubts that the Brazilian government is engaged in mass censorship. Indeed, the censorship by Brazil’s Supreme Court is so extreme that even newspapers like the New York Times, which promotes US government censorship, have expressed outrage at the Supreme Court’s willingness to imprison journalists and podcasts, including “the Joe Rogan of Brazil.”

And now, my research makes clear that there is indeed a Brazilian Censorship-Industrial Complex, one which the U.S. government has advised and which the Open Society Foundations, along with eBay founder Pierre Omidyar, are financing.

This Censorship Industrial Complex even includes an NGO similar to the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH), which pressures corporate advertisers not to advertise on social media networks unless they censor more...

MORE IS PROVIDED IN MICHAEL’S PUBLIC SUBSTACK, this has been embedded just below…

Please subscribe now to support Public's award-winning investigative reporting…

Pedro Abramovay, Latin America Director for Soros’ Open Society Foundations

In the US, executive branch government agencies like the Department of Defense (DoD), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and Centers for Disease Control (CDC) demand censorship and work with NGOs to demand censorship.

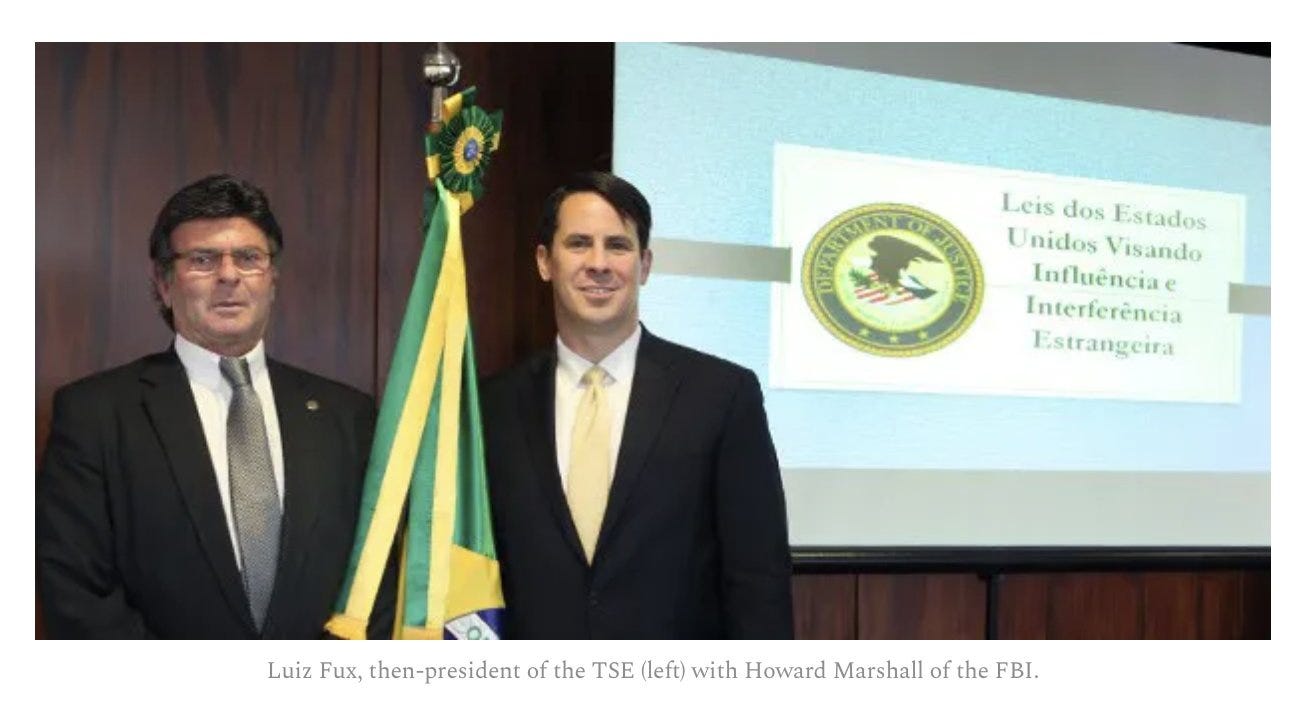

In Brazil, the judiciary branch, including the High Electoral Court, which oversees elections in Brazil, is the main driver of censorship. This High Electoral Court, the TSE, met with the FBI and a US Embassy Representative on March 5, 2018, to talk about censorship of “fake news.”

The push for censorship was thus eerily similar to the push for censorship in the US, Canada, the UK, and other nations around the world. The main difference is that in Brazil, the power is more in the hands of the judiciary, particularly the TSE, than the executive branch.

The TSE has been around for 90 years but its demand for censorship came in reaction to the Brexit referendum in the UK and the election of Donald J. Trump in the US in 2016. About a half year later, in mid-2017, the TSE judges expressed concern over the impact of “fake news” in Brazil. Interviews and documents show that the main concern was to avoid a "repeat of 2016," i.e., Trump's election and the alleged Russian Collusion.

In December 2017, TSE convened a public forum to discuss how to censor “fake news,” “disinformation,” and “bots.” The TSE created a special council to “conduct research” and “formulate strategies” to censor information it objected to.

Brazilian government censorship kicked into overdrive following the election of populist presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro in 2018. Government agencies, NGOs, and the news media claimed Bolsonaro had won through “disinformation,” just as they had claimed about Trump in 2020. In Brazil, they claimed the disinformation that elected Bolsonaro had traveled on WhatsApp, Facebook’s direct messaging app. This narrative served as a pretext for the initiation of the Brazilian Congress’ 2019 Fake News investigation.

In 2018, Brazil’s equivalent of the FBI, the Brazilian Intelligence Agency, or ABIN, and the intelligence sector of the Brazilian Army, worked with TSE to plan a censorship effort, according to minutes from the meeting.

Luiz Fux, then-president of the TSE (left) with Howard Marshall of the FBI.

FBI agents and US Justice Department officials participated in the TSE sessions. FBI’s Cyber Operations supervisor at the time and a Department of Justice agent specializing in counterespionage to thwart foreign interference attended. They shared insights into the efforts of the United States Department of Justice and the FBI in the battle against "fake news" Deji Okediji, a representative from the U.S. Embassy, was also in attendance.

On April 24, 2019, the TSE conducted an “International Seminar on Fake News and Elections,” which TSE ministers, including then-Justice Minister Sergio Moro, and representatives from the FBI all attended. Rogério Galloro, a former member of the Interpol Executive Committee, who now oversees various intelligence divisions within the TSE, also attended.

In Brazil, as in the US and Europe, the government is censoring populist politicians and their supporters. And just as DHS interfered in the 2020 elections, Brazil’s TSE interfered in the 2022 elections. The chief TSE judge, Alexandre de Moraes, formed a secret police specifically for the 2022 elections.

The Brazilian government funded the creation of censorship tools through the Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGV), one of Brazil’s leading universities and think tanks. Like the Stanford Internet Observatory, FGV sought to create a tool aimed at monitoring social media for “suspicious patterns” and “potential disinformation” during elections.

TSE sought a full range of censorship actions that mirror those used in the US and Europe. TSE endorsed FGV’s plan to create a blacklist, which it euphemistically referred to as a “registry of non-compliant sites.” TSE sought help from “Safernet,” an NGO, and “First Draft,” to create fake news blacklists. And just as Omidyar Network proposed ways for social media users to report other users to authorities, the TSE sought ways for users to report their fellow citizens to the TSE.

In October 2022, in the lead-up to the second round of the elections, the lawyer to President Lula claimed to have documented a "disinformation ecosystem" of Bolsonaro supporters. The TSE agreed and implemented mass censorship measures against Bolsonaro supporters.

In office, Lula has proposed a sweeping crackdown on speech. The government has proposed a special government speech regulator. Last November, it promoted censorship with the European Union. In December, the TSE announced its censorship plan, which will cover “hate speech” and anything that supposedly undermines democracy.

There are many other similarities between the crackdown in Brazil and other nations in the Western world. Just as the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) demand advertiser boycotts of social media companies so that they will censor more, Brazil has an NGO called “Sleeping Giants Brazil” (SBGR), inspired by a less prominent American group. It also lobbies for more censorship.

While Sleeping Giants portrays itself as a non-partisan movement against hate speech and fake news, all its targets are groups and personalities identified with the right, just like ADL and CCDH. Sleeping Giants Brazil received $700,000 from the Ford Foundation and the Open Society Foundation (OSF) in 2022 and 2023. It receives additional support and infrastructure from organizations sponsored by Soros and Omidyar.

Some NGOs and journalists raised the alarm. Jonas Valente, an NGO leader, expressed concern over the involvement of the Brazilian Army at one of the TSE forums. But mostly, the NGOs, heavily funded by Soros and Omidyar, went along with the censorship planning.

Pedro Abramovay, a Brazilian who serves as Director for Latin America at the Open Society Foundations, is an outspoken advocate of the Fake News Bill and a vehement critic of Bolsonaro. Abramovay champions the idea of amplifying the TSE's powers, specifically to address the issue of "disinformation" more effectively.

Soros is the largest sponsor of pro-censorship organizations in Brazil. In 2020, Open Society distributed around US$22 million to Brazilian organizations, many of whom have demanded censorship by social media platforms. Many of the organizations funded by Soros in Brazil support censorship, including the Fundação Getulio Vargas and First Look Institute.

Why has the scope, strategy, and funding of Brazil’s Censorship Industrial Complex largely been a secret until now? Part of the reason is that many documents were confidential until recently. Another part is that it has existed in plain sight under the name of “fighting misinformation,” which has constituted the public relations and “limited hangout” of information from the government. But another part of it is that the mainstream news media has supported its existence.

Protesters protest against the Superior Electoral Court that censored Brazil Parallel a radio program in Sao Paulo, Brazil, on October 25, 2022. (Photo by Cris Faga/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Brazil’s news media have promoted and defended censorship for several reasons. They view social media and independent journalism as an economic competitor. They are culturally and institutionally aligned with the government’s counterpopulism. They may be directly funded by the U.S. government, which has secretly funded foreign journalists for decades, including through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and which supported Brazil’s 1964 military coup.

Unfortunately, all the trends are going in the wrong direction. At this moment, the TSE is seeking more power. It wants to broaden its influence in future elections to target not just fake news but also "hate speech,” a completely subjective measurement. And TSE is seeking greater “international cooperation.” The United Nations, World Economic Forum, and other global bodies have prioritized “fighting misinformation” in 2024.

If there is hope for countering the Brazilian government’s censorship, it comes in exposing it. The TSE meetings in 2018 were intended to be confidential until 2023 but were disclosed in 2019 following public protests of censorship.

We need to understand the nexus between government and tech corporations. For example, at the 2018 TSE meeting, the FBI delegation was led by Howard Marshall, who was then director of the FBI's Cybercrimes Division. In July 2018, Howard Marshall transitioned to the private sector, joining Accenture as Director of Intelligence. Accenture is the largest Facebook partner for content moderation, with contracts worth US$500 million per year. Marshall did not respond to our request for comment.

And where Public has found evidence of ADL’s relationship with the FBI dating back at least 40 years, we did not find evidence of FBI ties to Sleeping Giants.

There is much to do in the short and long term. In the short term, we must defeat the “Fake News” censorship bill, end the government’s social media surveillance, and demand the declassification of government investigations. In the long-term, Brazil needs its own equivalent of a First Amendment to provide the free speech protections the creators of our constitution intended.

Most of all we need to change our view of the FBI, Brazil’s Supreme Court, and Soros. They’re not defending free speech, democracy, and “open societies.” They’re undermining them.

Please subscribe now to support Public's award-winning investigative reporting…

“Google, Facebook, Uber, WhatsApp, and Instagram provide registration data and phone numbers without a court order”

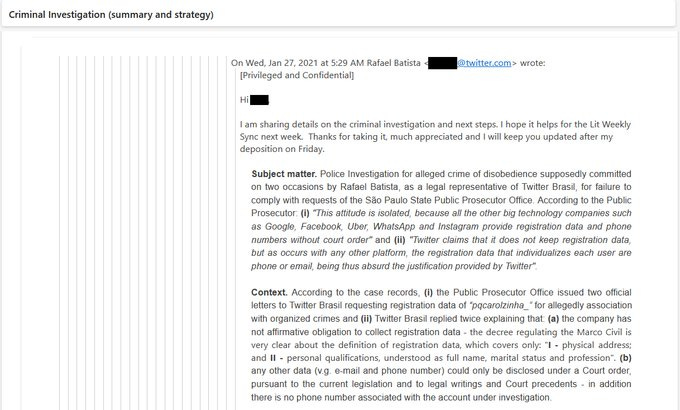

On January 27, 2021, Batista emailed his colleagues about a police investigation against him for refusing to give personal Twitter user data to the São Paulo State Public Prosecutor Office.

The Prosecutor claimed that Twitter’s “attitude is isolated because all the other big technology companies such as Google, Facebook, Uber, WhatsApp, and Instagram provide registration data and phone numbers without a court order."

But Twitter “has not [sic] affirmative obligation to collect registration data” explained Batista to the prosecutor and “there is no phone number associated with the account under investigation.”

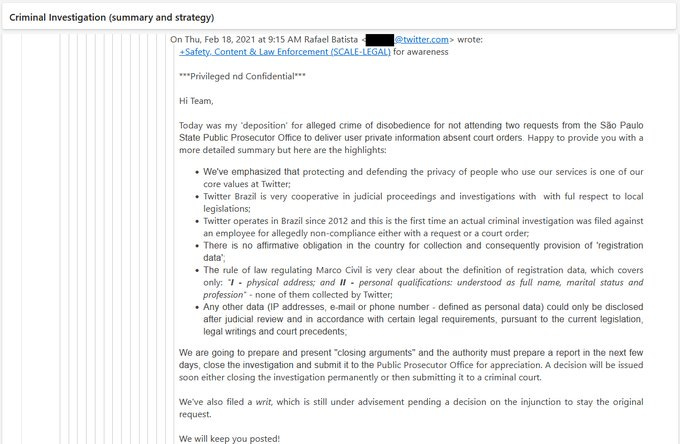

“This is the first time an actual criminal investigation was filed against an employee”

On February 18, 2021, Batista emailed his colleagues again to report back on his deposition. He said he told the prosecutor that “Twitter has operated in Brazil since 2012 and this is the first time an actual criminal investigation was filed against an employee for allegedly non-compliance either with a request or a court order.”

Batista said he pointed out that “There is no affirmative obligation in the country for collection and consequently the provision of 'registration data'."

Moreover, Brazil’s Internet privacy law, “Marco Civil… covers only: "I - physical address; and II - personal qualifications: understood as full name, marital status and profession" - none of them collected by Twitter.”

“We are unfortunately living strange times in Brazil.”

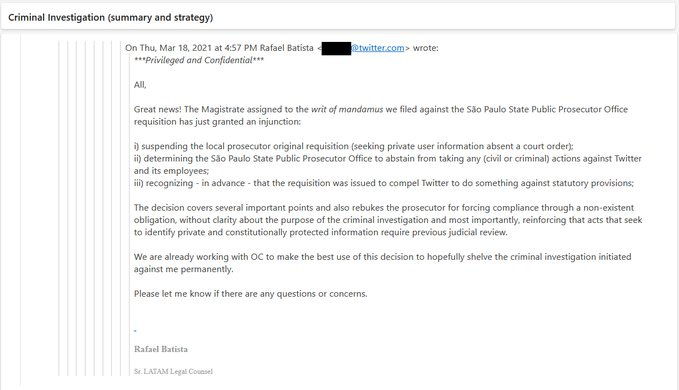

One month later, on March 18, Batista emailed his colleagues again, this time with, “Great news!” A judge rejected the prosecutor’s request for “private user information absent a court order” and also “rebukes the prosecutor for forcing compliance through a non-existent obligation, without clarity about the purpose of the criminal investigation and most importantly, reinforcing that acts that seek to identify private and constitutionally protected information require previous judicial review.”

A colleague of Batista, Regina Lima, replied to his email saying, “What Rafa forgot to mention is that the employee under threat here was him, the matter continued to escalate in a dangerous way and his resilience throughout the process was amazing.”

She added, “We are unfortunately living in strange times in Brazil. We are seeing a concerning trend on aggressive law enforcement requests and court orders restricting fundamental rights.”

“An unfortunate and surprising update”

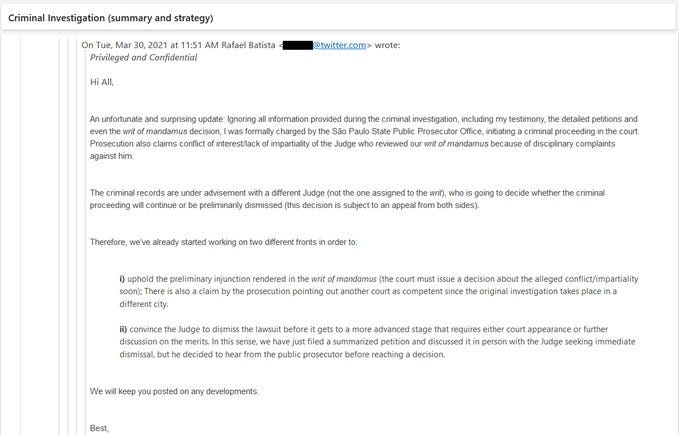

Then, on March 30, Batista emailed his colleagues again with “An unfortunate and surprising update”: the São Paulo State Public Prosecutor Office was back on the attack, “initiating a criminal proceeding” and claiming a “conflict of interest/lack of impartiality of the Judge.”

One week later, on April 5, 2021, Batista emailed his colleagues to say, “I am happy to share that we had great and relieving news…. The criminal court preliminary dismissed the charges against me mainly because it was not possible to identify any element of crime in my conduct.”

The ruling was because Twitter does not collect “registration data” of its users and the Marco Civil “clearly states that access to protected information such email - personal data - could only be done through specific judicial review.”

“Google Brazil… weakens our stance on privacy since we have always pushed back…

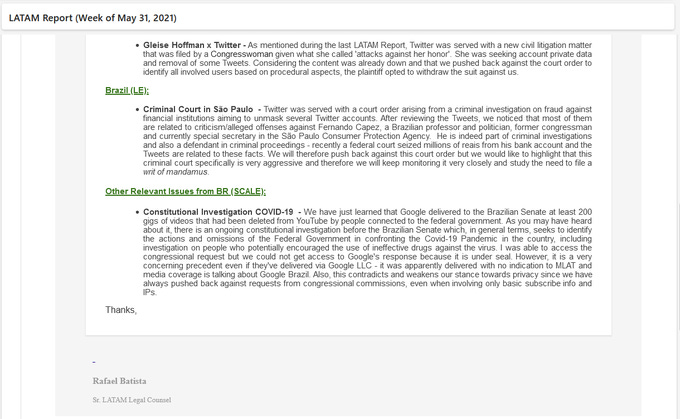

On May 31, 2021, Batista wrote to his colleagues to lament that “Google delivered to the Brazilian Senate at least 200 gigs of videos that had been deleted from YouTube by people connected to the federal government” related to a Brazilian Senate investigation of the government’s response to COVID-19.

Batista called Google’s actions “a very concerning precedent… that contradicts and weakens our stance towards privacy since we have always pushed back against requests from congressional commissions, even when involving only basic subscribe info and IPs….”

In the same email, Batista noted that a member of Congress named Gleisi Hoffmann, who presides over Lula da Silva’s Workers’ Party, and who had sued Twitter for “attacks against her honor,” seeking “private data and removal of some Tweets,” had finally dropped her lawsuit.

"Unmask several Twitter accounts..."

In the same email, Batista noted that a court in São Paulo had demanded that Twitter “unmask several Twitter accounts… related to criticism/alleged offenses against Fernando Capez, a Brazilian professor and politician, former congressman and currently special secretary in the São Paulo Consumer Protection Agency” who was “a defendant in criminal proceedings - recently a federal court seized millions of reais from his bank account and the Tweets are related to these facts. We will therefore push back against this court order…”

“We won't deliver any name at this stage…”

On June 11, 2021, Batista emailed his colleagues to say that the government had opened a criminal investigation against Twitter and that Brazilian “authorities are seeking the name and address of the person responsible for conducting the case internally at Twitter…”

Batista reassured his colleagues: “We won't deliver any name at this stage…”

“Even though the complaint is legitimate, the requests are unreasonable”

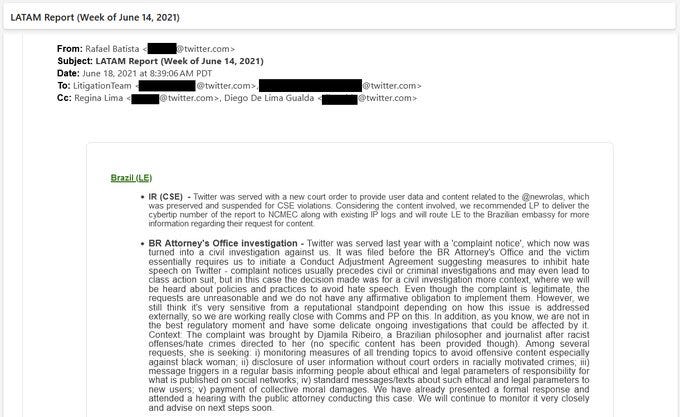

Batista emailed his colleagues on June 14, 2021, to say that “Twitter was served last year with a 'complaint notice', which now was turned into a civil investigation against us.”

Batista explained that “The complaint was brought by Djamila Ribeiro, a Brazilian philosopher and journalist after racist offenses/hate crimes directed to her (no specific content has been provided though). Among several requests, she is seeking: i) monitoring measures of all trending topics to avoid offensive content, especially against black women; ii) disclosure of user information without court orders in racially motivated crimes; iii) message triggers on a regular basis informing people about ethical and legal parameters of responsibility for what is published on social networks; iv) standard messages/texts about such ethical and legal parameters to new users; v) payment of collective moral damages. “

Another case related to an “extreme right” blogger “akin to Alex Jones” named Allan dos Santos. Twitter wanted to suspend the user, explained Batista, but “the user's history of litigating to keep their accounts active… we worry that the inherent messiness of the internal reviews [at Twitter] could make it challenging to explain the basis of a suspension action. Therefore we've agreed to let the strike system play out, and have us take action when it is clear and unambiguous upon their next violation of our rules, which is just a matter of time considering his list of violations and recent Tweets on COVID issues/misinfo…”

Information “related to @CarlosBolsonaro (president's son)”

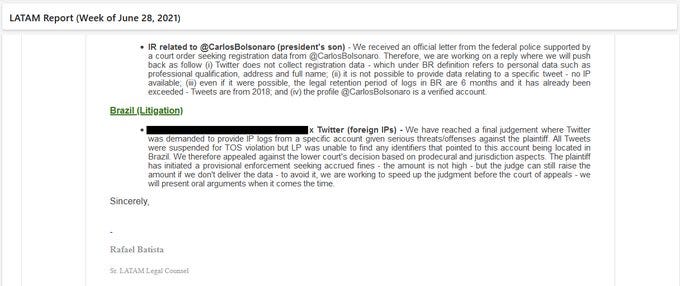

On July 2, 2021, Batista reported on an information request “related to @CarlosBolsonaro (president's son) - We received an official letter from the federal police supported by a court order seeking registration data from @CarlosBolsonaro. Therefore, we are working on a reply where we will push back as follows (i) Twitter does not collect registration data - which under BR definition refers to personal data such as professional qualification, address, and full name; (ii) it is not possible to provide data relating to a specific tweet - no IP available; (iii) even if it were possible, the legal retention period of logs in BR is 6 months and it has already been exceeded - Tweets are from 2018; and (iv) the profile @CarlosBolsonaro is a verified account."

“There is a strong political component with this investigation”

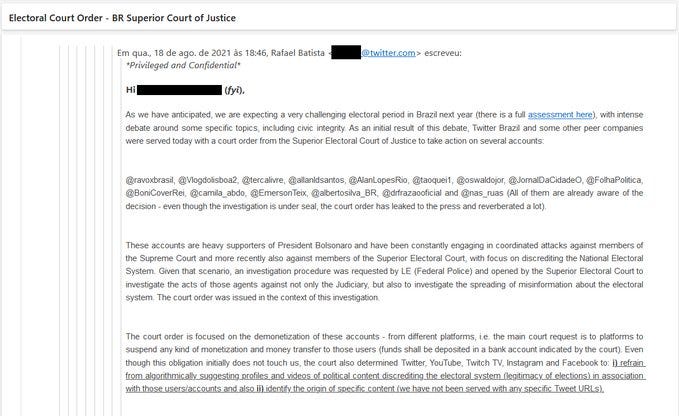

On August 18, 2021, Batista emailed his colleagues to say that the Superior Electoral Court has demanded that the accounts of “heavy supporters of President Bolsonaro” who “have been constantly engaging in coordinated attacks against members of the Supreme Court” and “Superior Electoral Court… The court order is focused on the demonetization of these accounts - from different platforms…”

These demands appeared to be politically motivated to target pro-Bolsonaro sentiment.

“Even though this obligation initially does not touch us, the court also determined Twitter, YouTube, Twitch TV, Instagram, and Facebook to: i) refrain from algorithmically suggesting profiles and videos of political content discrediting the electoral system (the legitimacy of elections) in association with those users/accounts and also ii) identify the origin of specific content (we have not been served with any specific Tweet URLs).”

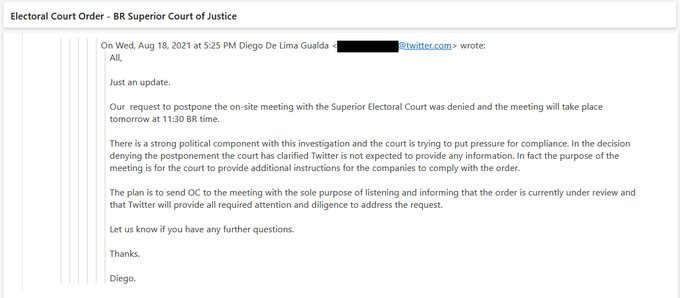

Twitter’s Head of Legal Diego de Lima Gualda, a colleague of Batista’s, responded by saying, “There is a strong political component with this investigation and the court is trying to put pressure for compliance.”

The “court wants to identify account handles… and also somehow reduce engagement”

Two days later, On August 20, 2021, Batista reported some alarming news about new demands from the Superior Electoral Court (TSE).

Batista reported that “it seems like the court wants to identify account handles that would have specifically added certain types of trending hashtags and also somehow reduce the engagement of specific content on the platform (ie. refrain specific accounts from being suggested to others.”

This represented a significant escalation in the court’s anti-democratic efforts.

Batista noted that “President Bolsonaro himself and several of his supporters are being investigated in this procedure (15 Twitter account handles have been provided so far).”

“We are going to push back”

Brazil’s High Electoral Court (TSE), which de Moraes controls, also demanded that Twitter reveal the identities of users. On October 25, 2021, Twitter’s senior legal counsel, Rafael Batista, emailed his colleagues to let them know that the TSE was “compelling us to track down and unmask users who used specific hashtags.”

The TSE’s request was illegal, noted Batista, and so Twitter would resist the court’s order. Batista said that Twitter was “going to push back” because there was “no evidence of illegality in the use of hashtags” and because the TSE was demanding “mass and indiscriminate disclosure of private user data, which characterizes a violation of privacy and other constitutional rights."

On November 26, 2021, the courts of Brazil issued sweeping censorship demands.

A court of appeals orders Twitter to “globally remove,” not just in Brazil, “specific URLs related to the plaintiff.”

The court claimed that Brazilians could find other ways to see the content, such as through a VPN, which masks a user’s location.

The court also sought to know the identities of users who were not in Brazil.

In another case, Twitter was “pushing back against an injunction that granted data provision (IP logs) to unmask 62 accounts that retweeted an original illegal content…” Of the 62 accounts, “8 accounts are not even located in Brazil…”

The Police are “under a lot of pressure from the Superior Electoral Court”

In March 2022, Twitter’s Head of Legal for Latin America saaid that he met with “the judge,” referring to de Moraes. He said he was surprised to find there the Federal Police (Brazil’s FBI) and technical court staff working on the hashtag investigation.

TSE pushed for private user data under the justification of “exceptional circumstances” and wanted to use Twitter as a crime precognition machine to “anticipate potential illegal activities.”

Two months later, Gualda said that the Federal Police “is under a lot of pressure from the Superior Electoral Court to provide tangible results for this investigation (remembering that in this procedure the Federal Police is supporting an investigation that is conducted by the Superior Electoral Court itself).”

“There is no reason for this lawsuit to be under court secrecy.”

Leading up to the 2022 presidential election in Brazil, TSE made censorship demands to prevent citizens from commenting on election policies and procedures.

On March 30, 2022, the day after de Moraes took office as president of the TSE, the TSE mandated Twitter to, within a week and under the threat of a daily fine of 50,000 BRL (US$ 10,000), supply data on the monthly trend statistics for the hashtags #VotoImpressoNAO (“PrinteVoteNo”) and #VotoDemocraticoAuditavel (“DemocraticAuditableVote”).

Additionally, the TSE demanded subscription information and IP addresses of users who used the hashtag #VotoDemocraticoAuditavel in 2021. Brazilians wanted to debate printouts to enhance their unique voting machines, but the TSE wasn’t happy about their cause and pressured Twitter to give up their personal data.

In an e-mail sent in November 2022, a Twitter lawyer detailed actions taken by Moraes and TSE during the presidential race. The judge wouldn’t explain why he ordered Twitter to remove Evangelical pastor André Valadão’s (@andrevaladao) entire account under a heavy fine.

Twitter “filed an appeal against the order”, pointing out they didn’t know why they were being ordered to do so, but complying. TSE would threaten Twitter to comply “in 1 hour” under an hourly fine of BRL 100,000 [US$ 20,000] to censor an inactive account for disinformation committed elsewhere.

TSE also targeted elected House members Carla Zambelli (@Zambelli2210) & Marcel van Hattem (@marcelvanhattem) for alleged misinformation, threatening a fine of BRL 150,000 (US$ 30,000) if Twitter did not comply within 1 hour. Twitter pushed back. Among other objections, it argued that “there is no reason for this lawsuit to be under court secrecy.”

“Unusual requests …. compelling us to provide… user data based on hashtag mentions”

On August 17, 2022, a member of Twitter’s legal team emailed the groups saying that Twitter “received a new court order” relating to “an inquiry with the aim to identify individuals/groups behind a potential coordination of efforts to attack the institutions and the electoral system across different platforms. President Bolsonaro himself is investigated in this process…”

She added, “We have received several unusual requests coming from this inquiry, the most recent relevant one compelling us to provide an undetermined amount of user data based on hashtag mentions. The hashtags concern a mobilization around the elections - roughly translated as #PrintedVoteNO; #DemocraticAuditableVote and #BarrosoInJail - Barroso is the former TSE President….According to the report we currently have, there were 182 tweets in the period of interest… We need the content, user handles, and respective BSI data ASAP…”

“TSE’s request is clearly abusive”

“TSE’s request is clearly abusive”, Brazilian attorney and legal scholar Hugo Freitas @hugofreitas_r told us, when asked about the situation. “Posting hashtags to promote legislative changes is completely appropriate for a democracy and it’s no crime predicted by Brazilian law.”

Three months after de Moraes became TSE’s president in August 2022, he demanded censorship.

Despite the fact that posting hashtags does not violate any specific legal statutes, Twitter complied with the court's demands to avoid substantial fines.

Brazil’s high court and Twitter removed political speech and penalized users for debating policies. In this way, the court appears to have interfered in a major presidential election.

Today: Fake News Bill For Censorship

Today, Brazil’s Censorship Industrial Complex is demanding that Congress pass “Fake News” censorship legislation. The bill would hold social media companies hostage if they didn’t comply with vague censorship requirements. The bill doesn’t define what “fake news” or “disinformation” are.

What the Fake News Bill would do is require social media platforms to pay news outlets for the right to distribute their content. This is the exact same approach being pushed by governments in Australia and Canada.

De Moraes, the TSE, and Brazil’s Supreme Court openly lobbied for the legislation.

The public revolted against the censorship bill, and Congress stalled the bill in May 2023.

Then, in February of this year, the TSE unilaterally implemented the legislation, usurping the role of Congress.

No Free Speech In An Election

TSE’s censorship is an attack on the democratic process. Elections can remain free and fair only if the public is able to debate and question election laws, systems, and results. If there ever is electoral fraud in Brazil, nobody will be allowed to talk about it, if de Moraes gets his way.

For centuries, candidates have complained that the election was stolen. Hillary Clinton claimed this in 2016, Stacey Abrams claimed this in 2018, President Donald Trump claimed this in 2020, and President Jair Bolsonaro claimed this in 2022.

De Moraes wants to make such speech illegal and punish social media platforms that don’t censor it.

The Solution: First Amendment-Level Protections For Brazil

Two legal scholars, Hugo Freitas and André Marsiglia, @hugofreitas_r and @marsiglia_andre, recently introduced new free speech legislation aimed at bringing free speech protections in Brazil to the same high standard as is held in the United States. The bill is a “Declaration of Rights of Freedom of Expression in Brazil.”

The bill seeks to proclaim a Declaration of Free Speech Rights in Brazil, which, if enacted, would roughly align Brazilian law to that of the United States in this regard.

It proposes to repeal the criminalization of speech in all but the most extreme instances, such as true threats or incitement to imminent lawless action. In contrast, conducts such as blasphemy, contempt of authority, or certain forms of hate speech and disinformation would cease to be criminalized. The protection of political speech is especially emphasized.

In tort cases, the bill seeks to reduce judicial discretion by laying out clearer standards for assessing if the speech is protected or crosses into illegal conduct. In particular, the bill repeals provisions that have been used by prosecutors and private associations to retaliate against speech by claiming compensatory damages, under allegations such as that it has caused offense to an unknown number of listeners or tarnished the reputation of broad categories of people.

Finally, the bill concerns itself with more modern forms of censorship targeting the internet. A blanket ban is imposed on the practice, now frequent in Brazil, of government blocking access to specific social media accounts in response to speech.

More subtle forms of internet censorship are also addressed. The government is barred from censoring speech indirectly under the guise of content moderation by private platforms, following in the footsteps of recent court decisions in the US. The bill reaffirms the provisions already in place in Brazilian legislation exempting social media platforms from liability for the speech of its users in response to attempts by the government to revoke those provisions so as to force social media companies to censor preemptively according to government wishes.

\ END